CHAPTER X OF POWER, WORTH, DINGITY, HONOUR, AND WORTHINESS

THE ‘Power of a man,’ to take it universally, is his present means, to obtain some future apparent good; and is either ‘original’ or ‘instrumental.’

‘Natural power’ is the eminence of the faculties of body or mind, as extraordinary strength, form, prudence, arts, eloquence, liberality, nobility. ‘Instrumental’ are those powers which, acquired by these or by fortune are means and instruments to acquire more, as riches, reputation, friends, and the secret working of God, which men call good luck. For the nature of power is in this point like to fame, increasing as it proceeds; or like the motion of heavy bodies, which the further they go make still the more haste.

The greatest of human powers is that which is compounded of the powers of most men, united by consent, in one person, natural or civil, that has the use of all their powers depending on his will such as is the power of a commonwealth. Or depending on the wills of each particular, such as is the power of a faction or of divers factions leagued. Therefore to have servants is power; to have friends is power; for they are strengths united.

Also riches joined with liberality is power, because it procureth friends and servants; without liberality, not so; because in this case they defend not, but expose men to envy, as a prey.

Reputation of power is power, because it draweth with it the adherence of those that need protection.

So is reputation of love of a man's country, called popularity, for the same reason.

Also, what quality soever maketh a man beloved or feared of many, or the reputation of such quality, is power, because it is a means to have the assistance and service of many.

Good success is power, because it maketh reputation of wisdom or good fortune, which makes men either fear him or rely on him.

Affability of men already in power is increase of power, because it gaineth love.

Reputation of prudence in the conduct of peace or war is power, because to prudent men we commit the government of ourselves more willingly than to others.

Nobility is power, not in all places but only in those commonwealths where it has privileges, for in such privileges consisteth their power.

Eloquence is power, because it is seeming prudence.

Form is power, because, being a promise of good, it recommendeth men to the favour of women and strangers.

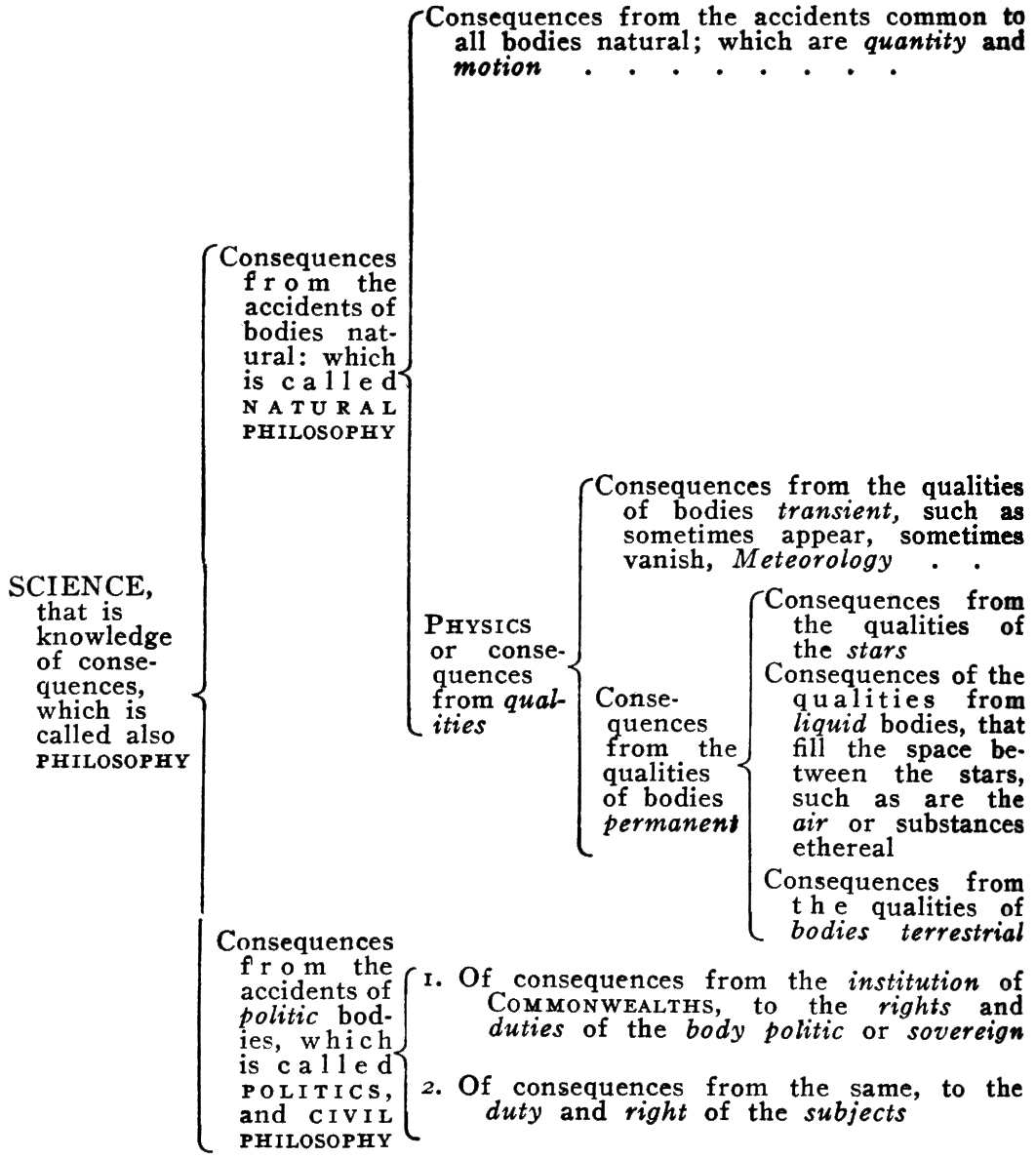

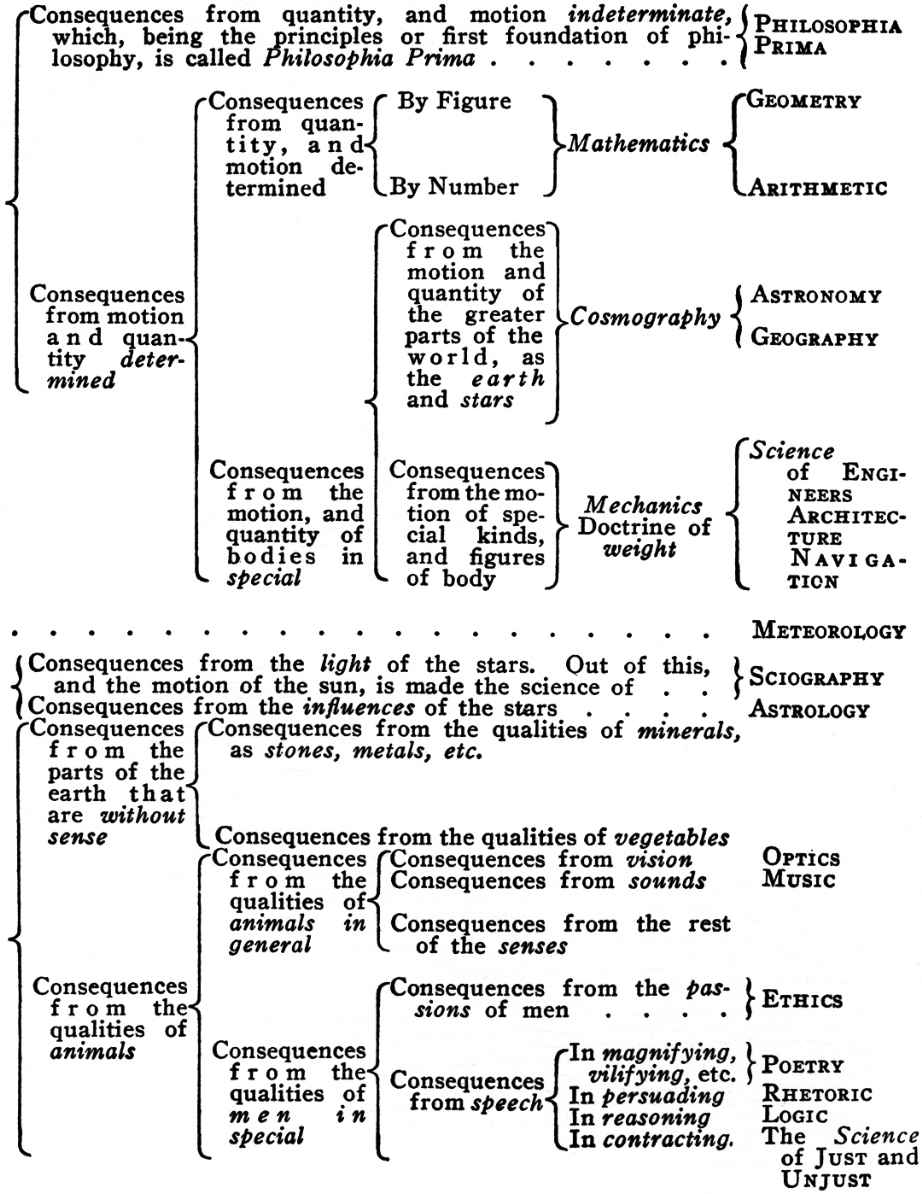

The sciences are small power, because not eminent and therefore not acknowledged in any man; nor are at all, but in a few, and in them but of a few things. For science is of that nature as none can understand it to be but such as in a good measure have attained it.

Arts of public use, as fortification, making of engines, and other instruments of war, because they confer to defence and victory, are power; and though the true mother of them be science, namely the mathematics, yet, because they are brought into the light by the hand of the artificer, they be esteemed, the midwife passing with the vulgar for the mother, as his issue.

The ‘value,’ or ‘worth,’ of a man is, as of all other things, his price; that is to say, so much as would be given for the use of his power; and therefore is not absolute, but a thing dependent on the need and judgment of another. An able conductor of soldiers is of great price in time of war present, or imminent; but in peace not so. A learned and uncorrupt judge is much worth in time of peace, but not so much in war. And, as in other things so in men, not the seller but the buyer determines the price. For let a man, as most men do, rate themselves [himself] at the highest value they [he] can, yet their [his] true value is no more than it is esteemed by others.

The manifestation of the value we set on one another is that which is commonly called honouring and dishonouring. To value a man at a high rate is to ‘honour’ him; at a low rate, ‘to dishonour’ him. But high and low, in this case, is to be understood by comparison to the rate that each man setteth on himself.

The public worth of a man, which is the value set on him by the commonwealth, is that which men commonly call ‘dignity.’ And this value of him by the commonwealth is understood by offices of command, judicature, public employment, or by names and titles introduced for distinction of such value.

To pray to another for aid of any kind is ‘to honour,’ because a sign we have an opinion he has power to help; and the more difficult the aid is, the more is the honour.

To obey is to honour, because no man obeys them whom they think have no power to help or hurt them. And consequently to disobey is to ‘dishonour.’

To give great gifts to a man is to honour him, because it is buying of protection and acknowledging of power. To give little gifts is to dishonour, because it is but alms and signifies an opinion of the need of small helps.

To be sedulous in promoting another's good, also to flatter is to honour, as a sign we seek his protection or aid. To neglect is to dishonour.

To give way or place to another in any commodity is to honour, being a confession of greater power. To arrogate is to dishonour.

To show any sign of love or fear of another is to honour, for both to love and to fear is to value. To contemn, or less to love or fear than he expects, is to dishonour, for it is undervaluing.

To praise, magnify, or call happy, is to honour, because nothing but goodness, power, and felicity, is value. To revile, mock, or pity, is to dishonour.

To speak to another with consideration, to appear before him with decency, and humility, is to honour him, as signs of fear to offend. To speak to him rashly, to do anything before him obscenely, slovenly, impudently, is to dishonour.

To believe, to trust, to rely on another, is to honour him, a sign of opinion of his virtue and power. To distrust, or not believe, is to dishonour.

To hearken to a man's counsel or discourse, of what kind soever, is to honour, as a sign we think him wise, or eloquent, or witty. To sleep, or go forth, or talk the while, is to dishonour.

To do those things to another which he takes for signs of honour, or which the law or custom makes so, is to honour, because in approving the honour done by others he acknowledgeth the power which others acknowledge. To refuse to do them is to dishonour.

To agree with in opinion is to honour, as being a sign of approving his judgment and wisdom. To dissent is dishonour, and an upbraiding of error, and, if the dissent be in many things, of folly.

To imitate is to honour, for it is vehemently to approve. To imitate one's enemy, is to dishonour.

To honour those another honours is to honour him, as a sign of approbation of his judgment. To honour his enemies is to dishonour him.

To employ in counsel or in actions of difficulty is to honour, as a sign of opinion of this wisdom or other power. To deny employment in the same cases to those seek it is to dishonour.

All these ways of honouring are natural, and as well within as without commonwealths. But in commonwealths, where he or they that have the supreme authority can make whatsoever they please to stand for of honour, there be other honours.

A sovereign doth honour a subject with whatsoever title, or office, or employment, or action, that he himself will have taken for a sign of his will to honour him.

The King of Persia honoured Mordecai when he appointed he should be conducted through the streets in the king's garment upon one of the king's horses, with a crown on his head and a prince before him, proclaiming ‘Thus shall it be done to him that the king will honour.’ And yet another king of Persia, or the same another time, to one that demanded for some great service to wear one of the king's robes, gave him leave so to do; but with this addition, that he should wear it as the king's fool; and then it was dishonour. So that of civil honour the fountain is in the person of the commonwealth, and dependeth on the will of the sovereign; and is therefore temporary, and called ‘civil honour,’ such as magistracy, offices, titles, and, in some places, coats and scutcheons painted; and men honour such as have them, as having so many signs of favour in the commonwealth: which favour is power.

‘Honourable’ is whatsoever possession, action, or quality, is an argument and sign of power.

And therefore to be honoured, loved, or feared of many, is honourable, as arguments of power. To be honoured of few or none, ‘dishonourable.’

Dominion and victory is honourable, because acquired by power; and servitude, for need or fear, is dishonourable.

Good fortune, if lasting, honourable, as a sign of the favour of God. Ill fortune and losses dishonourable. Riches are honourable, for they are power. Poverty, dishonourable. Magnanimity, liberality, hope, courage, confidence, are honourable, for they proceed from the conscience of power. Pusillanimity, parsimony, fear, diffidence, are dishonourable.

Timely resolution, or determination of what a man is to do, is honourable, as being the contempt of small difficulties and dangers. And irresolution, dishonourable, as a sign of too much valuing of little impediments and little advantages; for when a man has weighed things as long as the time permits, and resolves not, the difference of weight is but little, and therefore, if he resolve not, he overvalues little things, which is pusillanimity.

All actions and speeches that proceed, or seem to proceed, from much experience, science, discretion, or wit, are honourable, for all these are powers. Actions or words that proceed from error, ignorance, or folly, dishonourable.

Gravity, as far forth as it seems to proceed from a mind employed on something else, is honourable, because employment is a sign of power. But, if it seem to proceed from a purpose to appear grave, it is dishonourable. For the gravity of the former is like the steadiness of a ship laden with merchandise, but of the latter like the steadiness of a ship ballasted with sand and other trash.

To be conspicuous, that is to say to be known, for wealth, office, great actions, or any eminent good, is honourable, as a sign of the power for which he is conspicuous. On the contrary, obscurity is dishonourable.

To be descended from conspicuous parents is honourable, because they the more easily attain the aids and friends of their ancestors. On the contrary, to be descended from obscure parentage is dishonourable.

Actions proceeding from equity joined with loss are honourable, as signs of magnanimity; for magnanimity is a sign of power. On the contrary, craft, shifting, neglect of equity, is dishonourable.

Covetousness of great riches, and ambition of great honours are honourable, as signs of power to obtain them. Covetousness and ambition of little gains or preferments is dishonourable.

Nor does it alter the case of honour whether an action, so it be great and difficult and consequently a sign of much power, be just or unjust; for honour consisteth only in the opinion of power. Therefore the ancient heathen did not think they dishonoured, but greatly honoured, the gods when they introduced them in their poems committing rapes, thefts, and other great but unjust or unclean acts; insomuch as nothing is so much celebrated in Jupiter as his adulteries; nor in Mercury as his frauds and thefts: of whose praises, in a hymn of Homer, the greatest is this, that, being born in the morning, he had invented music at noon, and before night stolen away the cattle of Apollo from his herdsmen.

Also amongst men, till there were constituted great commonwealths, it was thought no dishonour to be a pirate or a highway thief, but rather a lawful trade, not only amongst the Greeks but also amongst all other nations as is manifest by the histories of ancient time. And at this day, in this part of the world, private duels are and always will be honourable, though unlawful, till such time as there shall be honour ordained for them that refuse, and ignominy for them that make the challenge. For duels also are many times effects of courage, and the ground of courage is always strength or skill, which are power; though for the most part they be effects of rash speaking and of the fear of dishonour, in one of both the combatants, who, engaged by rashness, are driven into the lists to avoid disgrace.

Scutcheons and coats of arms hereditary, where they have any eminent privileges, are honourable; otherwise not: for their power consisteth either in such privileges, or in riches, or some such thing as is equally honoured in other men. This kind of honour, commonly called gentry, hath been derived from the ancient Germans. For there never was any such thing known where the German customs were unknown. Nor is it now anywhere in use where the Germans have not inhabited. The ancient Greek commanders, when they went to war, had their shields painted with such devices as they pleased; insomuch that an unpainted buckler was a sign of poverty and of a common soldier; but they transmitted not the inheritance of them. The Romans transmitted the marks of their families: but they were the images, not the devices, of their ancestors. Amongst the people of Asia, Africa, and America, there is not, nor was ever, any such thing. The Germans only had that custom; from whom it has been derived into England, France, Spain, and Italy, when in great numbers they either aided the Romans or made their own conquests in these western parts of the world.

For Germany, being anciently, as all other countries in their beginnings, divided amongst an infinite number of little lords, or masters of families, that continually had wars one with another, those matters, or lords, principally to the end they might when they were covered with arms be known by their followers, and partly for ornament, both painted their armour or their scutcheon or coat with the picture of some beast or other thing, and also put some eminent and visible mark upon the crest of their helmets. And this ornament both of the arms and crest descended by inheritance to their children; to the eldest pure, and to the rest with some note of diversity, such as the old master, that is to say in Dutch, the Here-alt, thought fit. But when many such families, joined together, made a greater monarchy, this duty of the Here-alt to distinguish scutcheons was made a private office apart. And the issue of these lords is the great and ancient gentry, which for the most part bear living creatures, noted for courage and rapine; or castles, battlements, belts, weapons, bars, palisadoes, and other notes of war; nothing being then in honour but virtue military. Afterwards not only kings but popular commonwealths gave divers manners of scutcheons to such as went forth to the war, or returned from it, for encouragement or recompense to their service. All which, by an observing reader, may be found in such ancient histories, Greek and Latin, as make mention of the German nation and manners in their times.

Titles of ‘honour,’ such as are duke, count, marquis, and baron, are honourable, as signifying the value set upon them by the sovereign power of the commonwealth; which titles were in old time titles of office and command, derived some from the Romans, some from the Germans and French: dukes, in Latin duces, being generals in war; counts, comites, such as bear the general company out of friendship and were left to govern and defend places conquered and pacified; marquises, marchiones, were counts that governed the marches or bounds of the empire. Which titles of duke, count, and marquis, came into the empire about the time of Constantine the Great, from the customs of the German militia. But baron seems to have been a title of the Gauls, and signifies a great man, such as were the king's or prince's men, whom they employed in war about their persons, and seems to be derived from vir, to ‘ber,’ and ‘bar,’ that signified the same in the language of the Gauls, that vir in Latin, and thence to ‘bero’ and ‘baro’ so that such men were called ‘berones,’ and after ‘barones,’ and in Spanish, ‘varones.’ But he that would know more particularly the original of titles of honour may find it, as I have done this, in Mr. Selden's most excellent treatise of that subject. In process of time these offices of honour, by occasion of trouble and for reasons of good and peaceable government, were turned into mere titles, serving for the most part to distinguish the precedence, place, and order of subjects in the commonwealths; and men were made dukes, counts, marquises and barons, of places wherein they had neither possession nor command; and other titles also were devised to the same end.

‘Worthiness’ is a thing different from the worth or value of a man, and also from his merit, or desert, and consisteth in a particular power or ability for that whereof he is said to be worthy: which particular ability is usually named ‘fitness,’ or ‘aptitude.’

For he is worthiest to be a commander, to be a judge, or to have any other charge, that is best fitted with the qualities required to the well discharging of it; and worthiest of riches that has the qualities most requisite for the well using of them: any of which qualities being absent, one may nevertheless be a worthy man, and valuable for something else. Again, a man may be worthy of riches, office, and employment, and nevertheless can plead no right to have it before another; and therefore cannot be said to merit or deserve it. For merit presupposeth a right and that the thing deserved is due by promise; of which I shall say more hereafter, when I shall speak of contracts.